By Noelene Cole, Lynley Wallis, Heather Burke, Bryce Barker and Rinyirru Aboriginal Corporation

A day after setting up camp near the dray track which connected Cooktown to the Palmer Goldfield in south-east Cape York Peninsula, Sub-Inspector O’Connor and 24 troopers of the Native Mounted Police (NMP) were attacked by ‘daring and war-like’ Aboriginal land owners (O’Connor 1880). Evidently powerful military rifles won the day as the Lower Laura NMP camp became a permanent fixture in the war to defeat Aboriginal resistance. As this police camp lasted for 20 years it is renowned for its longevity. However, the Aboriginal clans it displaced had a settlement history of tens of thousands of years.

In our fieldwork to investigate the NMP we surveyed and excavated the site (also known as ‘Boralga’) in its now peaceful setting in a remote part of Rinyirru National Park. Boralga lagoon, a habitat for water birds, fish, crocodiles, stray cattle and feral pigs, is a less desolate sight than the decayed remains of the NMP camp on the sand ridge (Figure 1). Although the footprint of the frontier settlement (ironwood posts, antbed floors, broken glass, buttons and bullets etc) is fascinating, perhaps the most striking cultural feature is the scatter of culturally modified (scarred) Cooktown ironwood trees.

Cooktown ironwood (Erythophleum chorastachys, also known as red ironwood) is a major species of tree in this locality (Still-Baker et al. 2019), and the Lower Laura culturally modified trees (CMTs) belong to remnant open woodland natural vegetation. We recorded 31 trees with 38 cultural modifications or scars (some trees have more than one cultural scar). To identify scars as ‘cultural’ we looked for tool marks. The scars vary in size and shape, reflecting the many possible purposes of removing wood or bark. To record them we noted as many features as possible – e.g. condition, shapes, dimensions and position. We then assigned scars to the four groups we describe below.

Sugarbag and Toe Hold Scars

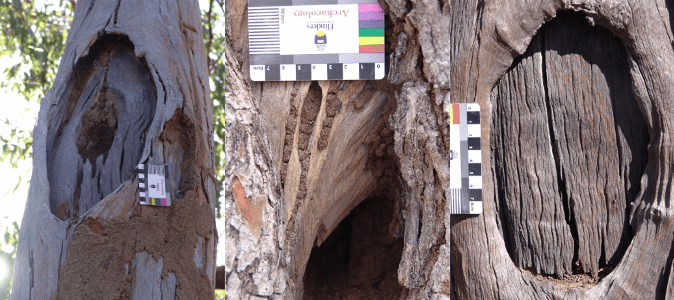

Here, as in other parts of Australia, native honey (sugarbag) is produced by native (stingless) bees (Trigona spp. and Austroplebeia spp.) that form large colonies and nest in natural cavities of trunks and branches of trees, which, in Cape York Peninsula are usually Cooktown ironwoods. Sugarbag was (and is) highly prized by Aboriginal people, who after locating a nest, would widen the opening to extract the honey and/or wax. The process created two types of scars: sugarbag scars around the opening, and sometimes small, shallow scars cut as toe holds to assist in climbing higher up the trunk to reach the nest (Figure 2).

As the sugarbag scars are relatively small, up to 10 cm long, they were probably cut by stone axes or tomahawks, which were either custom-made tools made by Aboriginal people from upcycled broken horse shoes, or were ready-made axes that, having been brought in by miners and others, were often salvaged by Aboriginal people (Figure 3).

Traditional Owners followed strict protocols in collecting and using sugarbag. The cultural significance of sugarbag is also shown in a language name: Awu Aloja, the ‘Sugarbag Bee Language’, a clan dialect of Kuku Thaypan language-complex, and in the many beehive paintings in local Aboriginal rock art.

Spearthrower (Woomera) Scars

Seven ironwood trees at Boralga have long, narrow scars that are typical of woomera scars found on old Cooktown ironwood trees (Figure 4). The tool marks are 10 cm or less in length, which means that the marks were cut by tomahawks or stone axes, sometimes assisted by a wedge to prise the wood from the tree. We also recorded a woomera scar with three sections, each cut to make a separate woomera (Figure 5).

On Cape York Peninsula, the spearthrower was the principal Aboriginal weapon, as reported by Sub-Inspector O’Connor (1877) ‘… they have only the wommera-spear as a weapon of defence or offence, but these they can throw nearly 200 … yards’. Different cultural groups had their own styles of spearthrowers, although Cooktown ironwood was the standard material for the blade. As in the case of sugarbag trees, Aboriginal people followed strict cultural protocols in cutting ‘woomera trees’.

Oval scars

Four trees have symmetrical, oval-shaped scars (mean length and width 38.5 x 14.5 cm). One well-preserved scar with a distinctive, light red face resembles the cultural scar sketched by O’Connor in his 1877 report (Figure 6). Oval scars like this are associated with removing wood to make small tools for shaping resin (Morrison et al. 2012), smoothing down the edges of spears, and with the removal of wood and bark to make traditional medicine for treating wounds and sickness.

‘Slab’ Scars

Seven trees at Boralga have conspicuous, sometimes multi-faceted scars created by cutting (adjoining) sections or panels of wood from the trunk (see Figure 7). The number and size of sections varies. The tool marks are usually longer than 10 cm, indicating that they were cut by long-handled axes (Figure 8).

As it is not clear who cut the slabs and why, we examined possible uses for them e.g. to make woomera blades, fish clubs or for building materials. It seems likely that they belong to the NMP camp phase, particularly as they were cut by long handled axes (Figure 8). If so, as the slab trees were not felled, they may have been cut by Aboriginal troopers.

Why are the CMTs significant?

Cooktown ironwoods grow slowly and often live to an advanced age; those with trunks more than 40 cm in diameter have an estimated age of at least 367 years (see Taylor et al. 2002). As the CMTs at Lower Laura are of this size or larger, they are likely to have been mature, established trees well before the invasion in the 1870s. As many of the cultural scars date from that time, the CMTs are valued testimonies to the Old People (the ancestors) of contemporary Traditional Owners, and of ongoing traditional connections with the land.

The different marks made by stone axes, tomahawks and long handled axes record a scenario of land use, as we described in a detailed paper just published by our team (Cole et al. 2020). Along the timeline, Aboriginal people are using stone axes and tomahawks in traditional ways on the Laura River floodplain. The long handled axe marks and evidence of a new way of removing wood reflect how the land was transformed by colonial occupation, including establishment of the police camp (Figure 9).

The CMTs have survived the frontier war, impacts of the NMP camp, the cattle industry, bushfires, tropical cyclones and termite attack. This is due to the durability of Cooktown ironwoods, the sustainable land practices of Aboriginal people and the environmental protections given by the national park. However, as the trees are very old and extremely vulnerable, it has been crucial to document them before it is too late. Although the work has been challenging due to the very weathered state of the cultural scars, it has provided important data for managing the values of Rinyirru National Park.

References

Cole, N., L. A. Wallis, H. Burke, B. Barker and Rinyirru Aboriginal Corporation 2020 ‘On the brink of a fever stricken swamp’: culturally modified trees and land-people relationships at the Boralga Native Mounted Police camp, Cape York Peninsula. Australian Archaeology, DOI: 10.1080/03122417.2020.1749371

Morrison, M., E. Shepard, D. McNaughton and K. Allen 2012 New approaches to the archaeological investigation of culturally modified trees: a case study from western Cape York Peninsula. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 35:17–51.

O’Connor, Stanhope 1877 Letter to Police Commissioner 1/12/1877 and plan of police reserve on the Laura River. Queensland State Archive A/40117 File 1449. File 1449, 4072/77

O’Connor, Stanhope 1880 Black v. White. Letter to the Editor. The Brisbane Courier, 20 December 1880, p.3.

Still-Baker, L., K. Sellars, T. Williams, S. Simon-Harrigan, J. Harrigan 2019 Vegetation Site Assessment – Boralga ‘Native Mounted Police’ site. Unpublished report prepared by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service and Partnerships and Rinyirru (Lakefield) Aboriginal Corporation in association with archaeological survey of Boralga 2016-2019.

Taylor, R., J. Woinarski, C. Hempel and G. Cook 2002 Ecological sustainability of timber harvesting in the Northern Territory. In R. Taylor (ed.), Ironwood Erythophleum chlorostachys in the Northern Territory: Aspects of its Ecology in Relation to Timber Harvesting, pp.121–136. Palmerston: Parks and Wildlife Commission.

Another cracking article, with some beaut illustrations too.